lalela uLwandle

Lalela uLwandle is a research-based theatre project that makes visible stories of living with the ocean that are seldom seen or heard in the public domain. Lalela uLwandle means “Listen to the Sea” in isiZulu. At some point in our lives, many of us have picked up a large shell and placed it against our ears to hear the sound of the oceans within it. It is this image that we invoke in this project, of standing quietly on the beach and listening to the stories of the ocean, and the people who have an intimate relationship with it. Weaving the stories, histories and contemporary concerns of diverse South African coastal communities into an Empatheatre production, Lalela uLwandle explores themes of intergenerational environmental injustices, tangible and intangible ocean heritage, marine science and the myriad threats to ocean health. Lalela uLwandle is an invitation to a participatory public conversation on ocean governance in South Africa. It is funded under the One Ocean Hub, a five-country hub of researchers exploring more democratic methods of engagement in ocean governance.

Lalela uLwandle tells the stories and family histories of three people: Nolwandle a marine educator whose mother is a Zionist and grandmother a sangoma; Niren a young environmental activist whose family has a long history of seine-net fishing brought here from India; and Faye a retired marine biologist living on the South Coast, reflecting on her role in science and activism. Audience members sit in a listening circle with the actors and bear witness to these intergenerational stories of the sea. The stories recount how the ocean is linked to various livelihoods, medicine and healing, scientific awe, study and wonder, and to spiritual connections with ancestors and loved ones who have died. In the telling, it deals explicitly with acts of past and present power and exclusion in South Africa. It performs the painful experiences of forced removals along the KwaZulu Natal coastline under apartheid, which robbed both Zulu people and Indian fishers from a life on the coast. It explores how extractive mining on land and sea, as well as industrial fishing continue to create forms of oppression and exclusion in South Africa. It also performs the tensions between environmental justice and environmental conservation, so frequently played out in real life when local people are restricted from accessing heritage and livelihood sites in Marine Protected Areas. Post-performance facilitated discussions make space for the audience members to share any questions, comments, and concerns.

Lalela uLwandle was inspired by a meeting between community representatives from multiple small towns along the KwaZulu Natal coast, and the Petroleum Agency South Africa (PASA - the agency responsible for the promotion, regulation and sustainable development of oil and gas in South Africa), in late 2018. At the meeting it was clear that many people who live along the coast feel that their voices are not heard when they express concerns about developments related to the Blue Economy; in this case, the granting of offshore exploratory oil and gas drilling licenses by PASA off the coast of KwaZulu Natal. The ‘community’ was treated as a homogenous group with one voice and one narrative of ‘opposition to development’, when in reality the ‘community’ consists of a wide range of worldviews, agendas, concerns and historical claims. In consultation with civil society partners (notably the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance (SDCEA) and groundWork), we identified this as symptomatic of a larger lack of meaningful participation in environmental decision making and ocean governance. The Lalela uLwandle team set out to share the diverse and nuanced relationship(s) people have with the sea, and to create an alternative space for participatory conversations about ocean governance. South Africa’s current Marine Spatial Planning Act and the Blue Economy policy framework largely overlook the intangible cultural and spiritual meanings of ocean heritage. The play opens up the possibility of more democratic ocean governance; to gather and share experiences, concerns and views of the oceans that move policy beyond economic and narrow conservation concerns.

The Lalela uLwandle project team explored in depth how different coastal people make sense of their relationship with the ocean. The participants included small-scale and subsistence fishers, marine scientists, academics, civil society activists, Zionists, marine educators at the aquarium and sangomas. Using Empatheatre’s research-based methodology, these diverse stories of the sea were woven together with archival material into the Lalela uLwandle theatre production. The opening research question to participants was a simple one: What are your first memories of the sea? The symbolic, scientific and spiritual meanings of the oceans, whilst different depending on your positionality and context, are important aspects of understanding humans’ relationship with the oceans. Memories, belief systems, stories and myths are powerful ways in which we not only make sense of our world, but choose to act on, and in it. For ocean orientated policy frameworks to be responsive and relevant to the needs of all species, including humans, it is critical that meaning-making of different kinds are considered.

In October 2019 Lalela uLwandle toured 6 small towns on the KwaZulu-Natal coast, with a final week's run in the city of Durban. Audiences consisted of the general public, as well as strategically invited guests from government, civil society, small-scale fisher associations, marine scientists and conservation officers. Each play is followed by a facilitated post-performance discussion with the audience. In many of these discussions’ audience members grappled with what it means to think collectively in a time of climate change and ocean degradation. They asked of themselves and fellow audience members how the injustices and inequalities in our past, and in our present, should shape our thinking of ocean governance in South Africa. Frequently audience members emphasised how different intangible heritages must be included in policy decision-making about the seas. Post-performance discussions became a tribunal space for sharing testimonies of oppression, and concerns around profit-seeking in the ocean. They were also importantly spaces in which the participants experienced how different ways of seeing, and being, do not necessarily preclude connections and solidarities for ocean health.

Lalela uLwandle had wide media coverage as the themes of the play was a topical issue. The tour aligned closely with the appeal deadline for the oil and gas offshore drilling decisions in KZN. A total of 17 articles on Lalela uLwandle in print were identified, and reached 451 002 people. Radio broadcasts on the play reached an additional 171 000 people in Kwa-Zulu Natal.

Through the connections made between audience members and the researchers involved in the development of the play, a nascent network with a shared concern for coastal justice was formed. In this way, the play (and the dialogues and learning that the play catalysed) has formed the basis for a ‘Coastal Justice Knowledge Action Network’, made up of civil society, academic researchers, marine scientists, lawyers and others, to respond pro-actively to emerging developments in the Blue Economy that threaten social and environmental justice.

The Lalela uLwandle production has since left the Kwa-Zulu Natal borders from where the stories emerged, and interacted with other fishing cooperatives and groups, as well as other scientists, activists and practitioners in the Eastern Cape. Prior to the COVID 19 pandemic Lalela uLwandle was scheduled to host shows, and post-show tribunals at the United Nations Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Portugal in June 2020 – as well as shows and tribunals with the South African Marine Sciences conference, and the National Marine Spatial planning committee in South Africa. These events have however been postponed till 2021/2022. In the interim we are building a podcast version of the play, a ‘radio-drama’ adaptation of the production, and will be hosting online discussions with UN fellows and decision makers in June 2020.

Nolwandle: Beside my Gogo’s village, there used to be a lagoon that ran into the sea where the community would fish. (She casts a seine- net across the stage) But one morning a fisherman pulled his net to the shore only to discover inkosazana, (a half-human, half-fish creature) who was very angry. This creature demanded that the fisherman set her free and never speak a word to anyone in his village about their meeting. But the fisherman was too frightened to listen, he dropped what he was doing and ran back to the village telling everyone there what had just happened.

When Gogo arrived at the lagoon edge to see if the man was speaking the truth, inkosazana called her closer and whispered…

She appears, faintly lit, under the net as the creature gasping for breath and frantically trying to claw it’s way out.

“Release me to the water now and carry this message to the fisherman who broke his promise to me. Tell him, in order to keep the peace between those who dwell on the land and the sacred ones who live in the sea, he must sacrifice a white cow on the water’s edge.”

She returns to the narrator.

After uGogo had released inkosazana, she rushed back to the village and demanded that the fisherman carry out the sacrifice…. but he laughed at her and went back to drinking his beer with the other men. (Pause) It was that man’s pride, Gogo always said, that was to curse our community in the end.

Niren: It frustrated my father to imagine the sort of abundance his grandparents had once enjoyed. Back in the day, it was said there were more fish in that sea than there were grains of sand on the Durban beaches. Some days it would all get too much and he would throw down his rod…. kick his chair across the beach.

He kicks the camping chair across the stage and paces the middle of the circle.

“What’s the blaady point of me sitting here with this measly rod and waiting for my Prodigal to bite, when everything’s been taken already! First it was the trawlers and now every day it’s something new. The government is selling our coastlines for mining, dumping their waste and shit in the water and thinking us fisherfolk don’t notice. The sea remembers my boy, it doesn’t keep secrets….in the end it throws everything back at us and it’s suffering now. (beat) So now we can crack coconuts till our heart's content, we can light camphor’s and candles and send them out to sea … but it doesn’t make a difference. (beat) And it’s not that the Gods aren’t listening… they aren’t the ones failing us here. It’s the blaady people who are the problem. (beat) You see this beach we are sitting on Niren…. It’s called the Bay of Plenty right? Back in my father’s day it might have been the case, but now…now we should just write it off as the Bay of empty.

Faye: David’s depression deepened every time he would watch the news or catch sight of the headlines…. At one of the last PASA meetings we had attended together, he had lost his cool.

“Our climate change science speaks unequivocally to the horrors that lie ahead…we are talking imminent collapse of whole eco- systems and yet still you people continue to prioritize these forms of extractive plunder…. acting as if there is NO real crises. As a scientist, I am here today, to tell you all, that what we are up against, constitutes a very real crisis.”

Nolwandle: In the final years of Gogo’s life, she had begun to suffer from terrible nightmares. This was during the time many of the communities around us were being relocated from living beside the ocean to areas inland. The apartheid government arrived and told our grandparents that they would need to be moved away so they could “stabilize” the sand dunes and that when they were we finished we would be moved back to the land.

But it was all a lie, there was nothing wrong with our sand dunes. Later we learnt that these companies had bribed the chiefs to keep the truth from us. They had known all along. By the time we had all realized what was happening the mining trucks were already lined up along our beaches… and with them, came the curse of inkosazana.

Niren: “… but hey Niren… soon white folks, fond of the old sea side picnic and yacht races began to complain about the “Salisbury eyesore”. The fisher folk community, they claimed spoiled the pretty postcard views, reeked of rotten fish and robbed the bay of its stocks. And you know European members of the Durban angling club signed petitions and bombarded the harbor authority with them. Soon new restrictions were put in place, along with an array of licenses which they knew, they knew our people could never afford. So you know what Kandasamy did? He formed one of Durban’s first unions to protest against the laws being imposed on them. (beat) But despite their attempts to save Salisbury island, by the turn of century it was already a thing of the past”.

Faye: (Still as David growing increasingly worked up) “… We can no longer value our oceans for their short-term material or monetary gains” David had protested... (beat) Does it mean nothing when I tell you that most of the oxygen you and I breathe comes from tiny little sea plants which contribute to between 50 to 85 percent of the oxygen in our Earth’s atmosphere. (beat) If we disturb this seabed, we may well destroy this system, and suffocate ourselves in the process(Pause) But the health of our seas…our children’s future has never been much of a priority has it? You people don’t need a clean ocean to profit from it! (Pause) And once you’re done, you just pack up and move to the next place…leaving wastelands for future generations to wallow in”.

Nolwandle: Traditional healers gathering muthi in the forests and rock pools were told by these conservation authorities that they now needed permits to abide by their ancestors wishes. When they of course ignored these rules, and continued as they always had in the past, many of them were arrested. Next came those fences rising all over the place... fences where there had never been before. When the people asked what these were about, the authorities told us these areas were now called marine parks…. special areas that would protect the sea-life and the white people who wanted to come on holidays to snorkel with them.

As she speaks, she removes several miniature homesteads with thatched roofs (Four cm high) from the central sand heap and begins placing them haphazardly around the circumference of the circle.

How could you tell such a thing to my Gogo! Can you imagine. She refused to listen, she kept going to the rock pools late at night when no one could see her. But on one of these evenings, she walked into a fence, a fence that cut her off from her pathways to the sea. Now, if Gogo wanted to get to the shore, she was told she would now have to travel the mining roads, like everyone else. Where would she find the time and money for this?

Niren: My Dad would always interrupt his storytelling to rant about how little had changed in his lifetime…

“You know what my favorite part is, it’s how the economists, and the government laanies like to keep calling the way we work ‘invisible economies’ – informal economies, things like that – but you know what that is Niren? That’s just a polite way of saying ‘We are not important’.

“The truth is the only thing these people care about; is how much money they can make from us. We are twenty something years into democracy, and we’re still being governed by apartheid fishing laws, the same laws our ancestors suffered under. (beat) Look here, say you are given a car license right, and the price of it goes up every year, and so you pay the monies like the good citizen you are - but then they turn around and tell you...you only allowed to use it to drive up and down your own blaady driveway!”

“And you know what the worst thing that Apartheid did to us as a people, was move you laaities away from the sea. Eh, when I was a youngster living in the village, we had purpose. We were far too busy fishing to get caught up in things like gangs and whoonga. And we had respect too. We never saw fishing as a free for all because one person’s greed would be the cause of many other’s suffering. Ja man back in the day, we let the season dictate what we put on our plate.

Faye: And as they escorted us out of the meeting, David had bellowed over his shoulder: “Does no one remember the explosion on the DeepWater Horizon in New Mexico? Millions of liters of oil choking eighteen thousand kilometers of ocean… an area twice the size of KZN! What’s to say that what happened in the Gulf, couldn’t happen along this coastline and when it does…. nothing will survive.”

Nolwandle rises wearing a pair of oversized black gumboots and a mining helmet with search light attached. We hear the rattle of mining machinery and heavy duty trucks. She stalks the circle and begins crushing the little homestead miniatures beneath her boots. Once she has destroyed the village, she then transforms into the grandmother character, setting eyes on the scene for the first time.

Nolwandle: One night Gogo, guided by her dreams, arrived at her beach but was forced to shield her eyes against the brightness of those lights. (The headlights of mining trucks blind her from the audience) Where before she had been greeted by the whispers of the ocean, now all she could hear and see were machines rattling into the night and swallowing up her beaches. (pause).

The rest of the actors in the circle, pick up their shoe boxes filled with shells and rattle them noisily. Music rises in intensity. Nolwande (as Gogo) lets out a wail, collapsing to the ground clutching handfuls of sand. Silence.

uGogo could no longer carry out her life’s calling. Without her muthi to heal them, the people in village grew sick and were forced to now consult the doctors in the towns. Eventually the voice which guided uGogo wami went silent.

“Massively powerful storytelling, I wish more ordinary people could see the play”

Gcina Mhlope

“A haunting, immersive and must-see production with superb heartfelt performances by three exceptionally accomplished actors, simple and effective lighting, wonderful imagery, sound and brilliant direction. A thought-provoking and hugely important piece of theatre.”

Publicity Matters.

"Funny, moving, thought-provoking and sobering. Three stories which lie at the heart of this experience makes use of simple props, a magical coral blanket, music and lighting to draw the audience deep into a world of scientific fact, traditional healing practices and the loves of those who have a deep relationship with the ocean."

The Witness

“It evoked a lot of emotions, such as anger, sadness and in the end hope! It was amazing I’ve never experienced anything like this before!”

Audience member on opening night

“In empathizing it made me reflect that it is so easy to be disillusioned and to stop feeling, we can’t let that happen!”

Audience member on opening night

“I am inspired a lot to be honest, this is our only home let us gather together to save it not just for us but also for our future generation”

School child from Mbazwana near Sodwana

“Fascinating and powerful... I was brought up with respect for the ocean, my mother would say when you enter the sea you are a guest of the fish, be a good guest!”

Audience member Port Shepstone

“This production has changed my ideas about what my actual purpose in this lifetime is. This has made me want to fight even harder at the preservation and conservation of our beautiful mother Ocean!”

Audience member, Durban

“I felt like I was living it. The way they were all concerned about the same thing, but yet they had different cultures, lives, backgrounds…was really amazing!”

Audience member Hluhluwe

“It felt incredibly soulful and powerfully educational yet without turning into a sermon…I think the beauty and genius of the 3 diverse characters and that it shows how deeply it affects all cultures, ages and status. I loved the humor in the characters”

Port Shepstone Audience

“Although they were three completely different stories and perspectives each one held something that sparked deep seated memories and emotions. It is important to remember how important the ocean is to all of us on so many levels”

Audience Member - Port Shepstone

Director:

Neil Coppen

Written:

Neil Coppen, with contributions from Helen Walne, Gcina Mahlope, Mpume Mthombeni, Dylan McGarry, Taryn Pereira, Kira Erwin.

Producer:

Dylan McGarry

Research:

Kira Erwin, Taryn Pereira, Dylan McGarry, Mpume Mthombeni, Jamie Alexander, Nomkhosi Xulu-Gama, Tanya Dayaram

Actors:

Alison Cassels, Elize Cawood, Mpume Mthombeni, Rory Booth & Kiroshen Naidoo

Design:

Dylan McGarry & Neil Coppen

Costumes:

Dylan McGarry & Diane Badenhorst

Lighting design:

Neil Coppen

Stage Managers:

Kelly Daniels and Zenzo Msomi

Sound Design:

Tristan Horton

Score:

Guy Buttery & Gary Thomas

Nolwandle (Mpume Mthombeni) cradling a cowrie shell, sets the scene: Every evening before bed, my Gogo would say: “Come child settle, close your mouth and open your ears. Lalela…lalela. Then she would begin by telling me my favorite bed-time story.” Pic by Val Adamson.

“For now, there are the cuttlefish eggs…the Mullens, each one waiting their turn. And when they’re all hatched, a low tide will be followed by a high tide, and the sea will rise up over the walls to fetch them. Tiny little creatures, moving with the currents who…when the time comes…. will know exactly what to do.”

Faye (Elize Cawood) looks to the future in the closing scene of Lalela uLwandle at the Theatre Arts Admin Collective in Cape Town, 2019. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

The magical Guy Buttery and his equally magical sitar accompanying the actors during a performance of Lalela uLwandle at the Theatre Arts Admin Collective in Cape Town 2019. The musicians Gary Thomas and Guy Buttery played instruments ranging from mbira, saw, guitar, sitar and percussion, working in close synergy with the performers to underscore the storytelling. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

“Our climate change science speaks unequivocally to the horrors that lie ahead…we are talking imminent collapse of whole eco- systems and yet still you people continue to prioritize these forms of extractive plunder…. acting as if there is NO real crises. As a scientist, I am here today, to tell you all, that what we are up against what constitutes a very real crisis.”

Faye (Alison Cassels) issues a stern warning in a scene from Lalela uLwandle. Pic by Val Adamson.

“But on one of these evenings, Gogo walked into a fence, a fence that cut her off from her pathways to the sea. Now, if Gogo wanted to get to the shore, she was told she would now have travel the mining roads, like everyone else. Where would she find the time and money for this?”

Nolwandle (Mpume Mthombeni) recalls how her Grandmother was forbidden from collecting muti along the coastline in a scene from Lalea uLwandle. Here the fishing-net from earlier scenes doubles as a fence ensnaring humans in its web. Pic by Val Adamson.

“Of all the skills Grandpa Subudu was most celebrated for, it was his ability to read the sea. During sardine and shad season, Subudu could be found riding the trains that ran along the coastline between Durban and Port Shepstone. He would lean out the carriage window, a cigarette dangling from his lips, his eagle-eyes trained on the sea, searching for the slightest ripple, the faintest stir.”

Niren (Rory Booth) recalls his Grandfather’s sublime talents in a scene from Lalela uLwandle at the Square Space Theatre in Durban. Pic Val Adamson.

A Hindu offering buoyed by the tides. Pic by Val Adamson.

Elize Cawood as Faye in the first iteration of Lalela uLwandle at the Theatre Arts Admin Collective in Cape Town, 2019. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

Mpume Mthombeni plays Nolwandle a marine educator who, with the help of a magical coral blanket, narrates an isiZulu ocean folk-tale written by storyteller Gcina Mhlophe. Pic by Val Adamson.

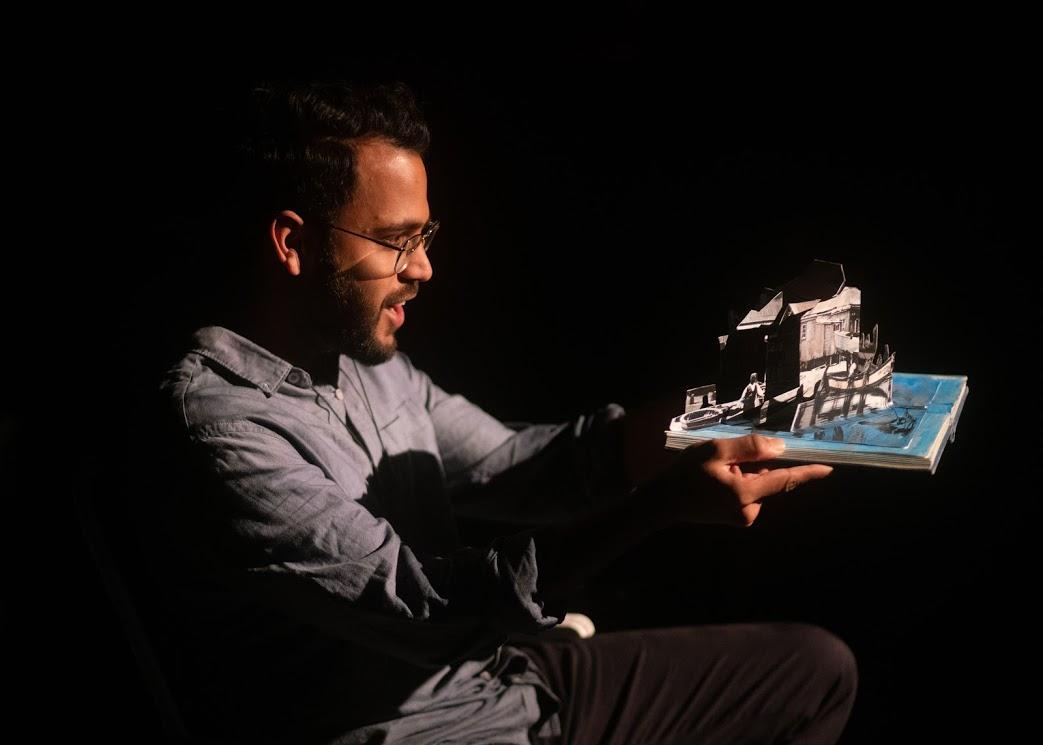

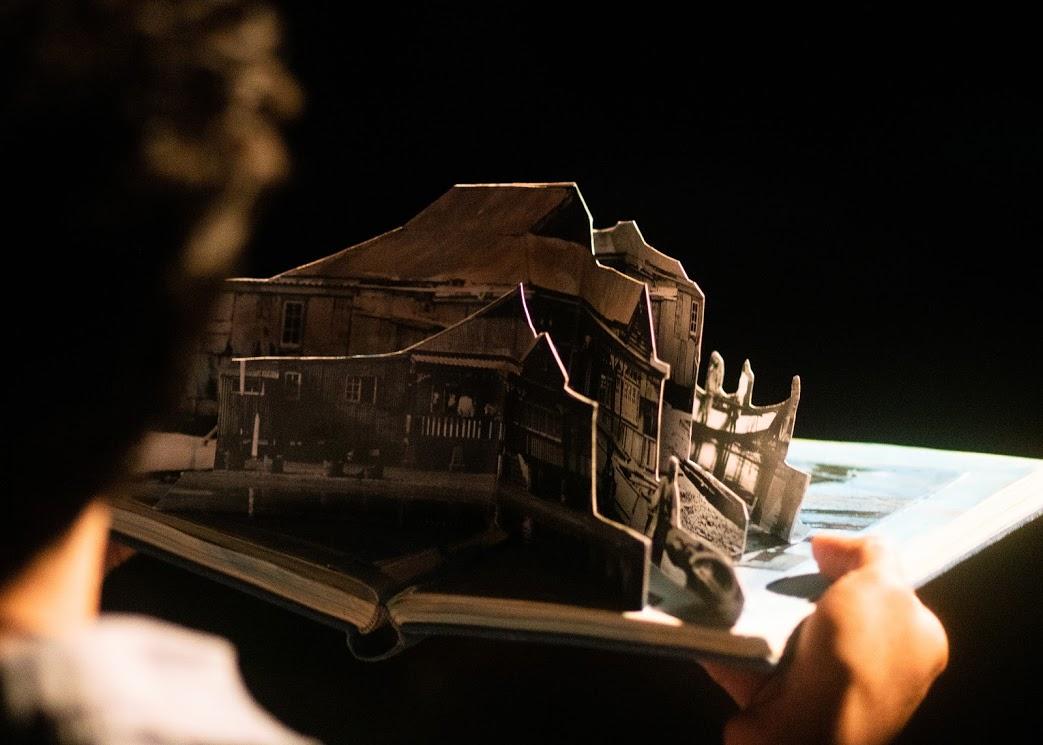

“Eventually my great grandparents were resettled on swamp-lands below the Fynlands station at the foot of the Bluff and they called this place The Village. My Dad said that Kandasamy rebuilt his house dismantling every window frame and roof-beam from the previous one. You see at the time of these removals, Papathi was heavily pregnant with their first child, and it was in this home, an exact replica of the last, that she gave birth to grandfather Subudu.”

Niren (Kiroshan Naaido) reveals a pop-up version his great grandfather’s fabled fishing residence during a performance of Lalela uLwandle at the Theatre Arts Admin Collective in Cape Town 2019. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

Niren (Kiroshan Naaido) reveals a pop-up version of his great grandfather’s fabled home during a performance of Lalela uLwandle at the Theatre Arts Admin Collective in Cape Town, 2019. Dylan McGarry meticulously created the pop-up house/book from original archive pictures of Salisbury Island fisher folk homes. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

Faye in the first iteration of Lalela uLwandle was portrayed by celebrated South African actress Elize Cawood working from a monologue written by South African author and journalist Helen Walne. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

Nolwandle (Mpume Mthombeni) nets a mythical ocean creature in a scene from Lalela uLwandle. Theatre Arts Admin Collective, Cape Town 2019. The fishing net used in this scene would later come to double as a fence that separates Nolwandle’s grandmother from the sea. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

Niren (Kiroshan Naaido) recalls the annual arrival of the sardines along the KZN Coast, a spectacle that has delighted generations of family members. The annual ‘Sardine run’ is a massive migration of sardines along the east coast of Africa, from north to south. The event brings massive trophic migrations of other species (sharks, whales, dolphins, seabirds). The event plays a vital role in local livelihoods, including non-extractives economies (tourism), and plays also a deep spiritual role in the annual calendar. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

Niren (Kiroshan Naaido) recalls his father’s love of fishing, weathering the east-coast thunder storms to net his prodigal son. A scene from Lalela uLwandle at the Theatre Arts Admin Collective in Cape Town, 2019. Pic by Retha Ferguson

Mpume Mthombeni transforms into a marauding machine destroying a village along Northern coast of KZN. Pic by Val Adamson.

Fact and fiction, myth and magic merge in a scene where Nolwandle (Mpume Mthombeni) tells the story of Inkosazana, (a half-human, half-fish creature) who gets trapped in a fisherman’s net and curses the fisher folk community for their disobedience. Pic by Val Adamson.

The stories featured in Lalela uLwandle recount how the ocean is linked to various livelihoods, medicine and healing, scientific awe, study and wonder, and to spiritual connections with ancestors and our loved ones who have died. In the telling it deals explicitly with acts of past and present power and exclusion in South Africa. Mpume Mthombeni as Nolwandle in a powerful scene from the production. Pic by Retha Ferguson.

Nolwandle (Mpume Mthombeni) whose mother is a Zionist and grandmother a sangoma ,prepares to perform a sea baptism by calling on her ancestors to calm the waves of the sea. Pic by Val Adamson.

Mpume Mthombeni features as marine educator and healer Nolwandle with her magical coral blanket at the Ushaka Marine World performance for marine educators’ in 2019. Pic by Kelly Daniels.

Weaving the stories, histories and contemporary concerns of diverse South African coastal communities into an Empatheatre production, Lalela uLwandle explores themes such as intergenerational environmental injustice, tangible and intangible ocean heritage, the myriad threats to ocean health and the lack of participatory democracy in ocean governance. Mpume Mthombeni features as Nolwandle during a performance of Lalela uLwandle in Port Shepstone 2019. Pic Kelly Daniels.

What are your first memories of the sea? Perhaps you remember your grandmother’s warnings about how you should be careful of the waves in case the ancestors came and took you. Or how your mother would through silver coins and prayers into the breakers on the shore. You may remember pictures of amazing deep-sea monsters from your science books, and dreamed about discovering uncharted benthic zones in a submarine. Your early memories could be of watching a baptism, or seeing your father light a candle in a coconut shell and send a blessing into the salty water. Or perhaps you were privileged enough to have the smell of coconut sunscreen, lollipops and collecting shells from rock pools on your annual family holiday as your first memory. The symbolic, scientific and spiritual meanings of the oceans, whilst different depending on your positionality and family beliefs, are important aspects of understanding humans’ relationship with the oceans. Memories, belief systems, stories and myths are powerful ways in which we not only make sense of our world, but choose to act on, and in it. In this photograph, Faye (Alison Cassels) recalls her delight at watching cuttle fish eggs hatch in a rock pool at a Sodwana Bay performance of Lalela uLwandle. Pic by Casey Pratt.

olwandle (Mpume Mthombeni) regales her audience with stories of oceanic wonder and subterranean awe during the Sodwana Bay performance of Lalela uLwandle, 2019. Pic by Casey Pratt

Mpume Mthombeni as Nolwandle’s Gogo, discovers mining machinery destroying her beach during a performance of Lalela uLwandle for high-school students in Zululand, 2019. Pic by Casey Pratt.

Pics by Kelly Daniels

he Lalela uLwandle project team set out to explore in depth how different coastal people make sense of their relationship with the ocean. The opening research question to participants was a simple one: What are your first memories of the sea? Pic by Casey Pratt.

Pic by Casey Pratt